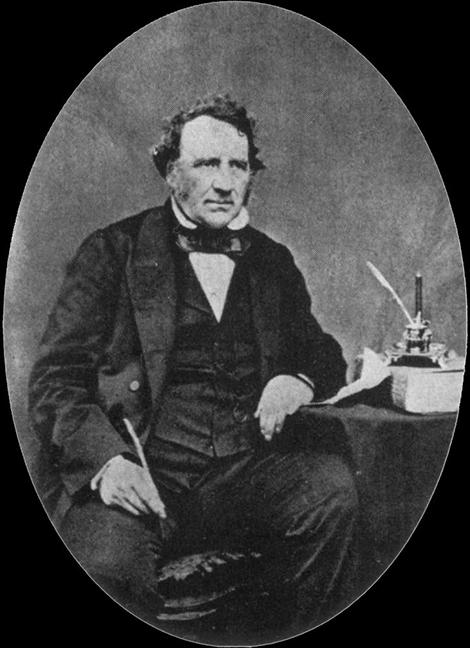

The phenomenal growth of London in the 19th century brought with it many problems, not least the ever present issue of traffic congestion. Charles Pearson, solicitor to the City of London, was one man who exercised his mind on the problem, issuing a pamphlet in 1845 entitled “Trains in Drains”, proposing a railway running underground from King’s Cross to Holborn, powered by air pressure.

It was such an ambitious and unusual proposal, stretching the technology of the time to its very limits, that it met with predictable opposition and scorn. The Times called it “an insult to common sense” while a Dr Cumming declared: “Why not build an overhead Railway?…It’s better to wait for the Devil than to make roads down into Hell”. For Sir Joseph Caxton, the problem was the concept of going underground. “People, I find”, he observed, “will never much go above the ground, and they will never go underground; they always like to keep as much as possible in the ordinary course in which they have been going”.

Undaunted, in 1846 Pearson presented a plan to Parliament for a line running longitudinally from King’s Cross to Blackfriars Bridge with a central hub at Farringdon which would replace all the other termini for trains entering and leaving London. A version of his proposal appeared in the edition of May 23, 1846, the Illustrated London News, showing two underground tunnels feeding a huge terminus at Farringdon with space to serve up to four railway companies and with goods stations just outside the main passenger station. The trains would be powered by air pressure.

Parliament rejected Pearson’s proposals, but by 1852 he had raised enough money to form the City Terminus Company to bring his dreams to fruition. Around the same time the Metropolitan Railway Company was formed with plans to connect Paddington to King’s Cross. Both companies presented their bills to Parliament, Pearson’s proposals once more rejected but the Metropolitan line given the go ahead. Pearson did get legislative approval in 1854 for a shorter line which ran to St Paul’s cathedral rather than Blackfriars Bridge.

Financial difficulties beset the Metropolitan Railway Company’s progress, forcing them to abandon any plans to go any further south than Farringdon. Still beset by financial difficulties they found a knight in shining armour from an unexpected quarter, Charles Pearson, who raised enough money to allow the Metropolitan Line to be completed and opened to the public on January 10, 1863. Pearson, though, never saw his dream of an underground railway in action, dying of dropsy in 1862.

The concept of an underground system took off with other lines built but the intrinsic problem of traffic congestion was never solved. In 1895 the enterprising The Picture Magazine published a puzzle entitled The Labyrinth of London which invited the reader “to enter by the Waterloo Road, and his object is to reach St Paul’s Church without passing any of the barriers which are placed across those Streets supposed to be under Repair”. Time or a reissue, methinks.